Making Good Once More

Some writers have called the BPF the “forgotten fleet.” In actuality, the Royal Navy’s contribution to the fight against Japan is fairly well remembered, mainly due to its presence at the Battle of Okinawa.2 Its participation in the raids against the Japanese Home Islands in the summer of 1945, however, is a different story.

Preparing for the Raids

The fleet was controversial. At the September 1944 Octagon Conference in Canada, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had offered President Franklin D. Roosevelt a Royal Navy fleet to fight against Japan. But Admiral Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations, did not want the British in the Pacific because of logistical issues. The Royal Navy’s equipment would require different spare parts and complicate supply lines. Domestic politics, though, required that Roosevelt say yes. He could hardly explain to the American public why he had turned down Allied assistance. Refusing to accept defeat, King stipulated that the British supply themselves. This requirement led to a great deal of wasteful redundancy and was not always honored in the breach.

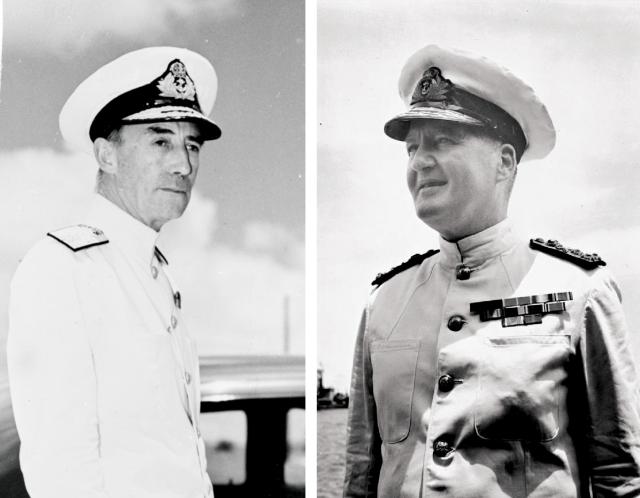

The commander-in-chief of the BPF was Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, but like Admiral Chester Nimitz, he was a deskbound commander. He gave the oceangoing command to Vice Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings with instructions that the fleet operate under an American admiral. Nimitz and Fraser had negotiated an arrangement on how the two navies would fight together. The BPF first saw combat during the Okinawa campaign and quickly proved itself, striking airfields on Sakishima Gunto, an island chain southwest of Okinawa. British carriers had an advantage that U.S. carriers lacked—armored flight decks. As a result, they suffered relatively little damage compared to U.S. ships when kamikazes struck them. All four BPF carriers were hit, but none was out of action for more than eight hours.3

Before the BPF next attacked the Home Islands, it first had to undergo refurbishing. New aircrews replaced the exhausted ones that had flown at Okinawa. With these new men, the British could put 255 planes in the air. The idea that they would be attacking the Japanese homeland was invigorating. Many of the pilots were from the British Dominions; the largest group came from New Zealand, while Australia and then Canada made up smaller contingents. With homes much closer to Japan than those of most other Britons, the Aussies and Kiwis had additional motivation to see the conflict through to the end. The pilots were young and inexperienced, but they were in better health than their colleagues from the United Kingdom.4

The Royal Navy provided the ships with new equipment, replacing the existing 20-mm guns with heavier 40-mm weapons. Problems remained, nonetheless. Engineers on board the carrier Implacable worked around the clock, and even while the ship was underway, to have her ready for combat. The air compressors on another carrier, the Indefatigable, stopped working while in port, and the ship would miss three days of combat.5

The British also developed new doctrine and procedures for the coming operations. The BPF adopted new antiaircraft tactics to thwart kamikaze attacks. The British even got better at logistics. Having operated in European waters, where the distances between bases were short, the Royal Navy had little expertise in underway sustainment operations, but on 13 July, HMS King George V fueled abeam of a tanker—the first time a British battleship had conducted the maneuver.6

The British joined the U.S. Third Fleet on 16 July and took the designation Task Force (TF) 37. “Everywhere you looked there were ships. You felt we couldn’t lose the war now,” one sailor on board the Implacable remarked. “In fact, we almost felt we were being big bullies.”7

A Meeting of Admirals

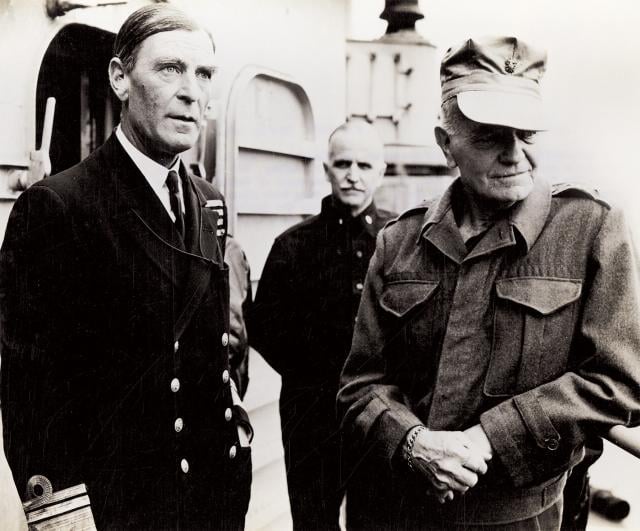

The U.S. fleet’s commander, Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., was one of the most popular naval heroes of the war—he appeared on the cover of Time magazine twice. Halsey was an aggressive, offensive-minded officer who tended to exploit opportunities when they presented themselves. He also did not want the Royal Navy in his fleet. In a message to Nimitz, he had proposed that he use the British Pacific Fleet on the flank of U.S. naval forces, with a significant gap between the two fleets.8

Nimitz quickly rejected this proposal. The British were to be part of Halsey’s fleet and treated like any other task force under his command. “Operate TF 37 separately from TF 38 [Halsey’s fast carrier task force] in fact as well as in name under arrangements which assign to Rawlings tasks to be performed but leave him free to decide upon his own movements and maneuvers,” Nimitz instructed.9 Fraser thought Halsey was being a bit legalistic about his agreement with Nimitz. “I myself did not mean this to preclude the possibility of a British task group operating in an American force,” Fraser informed the Admiralty.10

The BPF’s 16 July rendezvous with the Third Fleet was also the occasion of a meeting between Vian, Rawlings, and Halsey, who gathered on board the USS Missouri (BB-63) that morning. Halsey started the meeting, explaining that he intended that the strikes against the Home Islands weaken enemy resources before the invasion of Japan started. He then offered Rawlings three options:

1) The British could operate as a component element of the Third Fleet; Halsey would not give it orders but would give “suggestions,” which would allow the allies to concentrate their power against the Japanese.

2) Rawlings could operate as a semi-independent force separated from U.S. ships by 60 to 70 miles of ocean.

3) Task Force 37 could operate totally on its own.

Halsey recalled that Rawlings never hesitated in his response: “Of course, I’ll accept Number 1.”11

The British admiral had favorably impressed Halsey: “My admiration for him began at that moment. I saw him constantly thereafter, and a finer officer and firmer friend I have never known.”12

The British felt the same way. “It was apparent at once that we had struck lucky; there appeared in Halsey all the attributes of mind and body which go to make-up a great seaman, to which was added a wide humanity,” Vian stated years later. “He showed himself fully aware of our difficulties, and from that moment onwards, by kindly word or deed, he availed himself of every possible opportunity to offer encouragement and to smooth our path.”13

The Mission and a Problem

The military mission of the U.S. Third and British Pacific Fleets was fivefold: reduce enemy tactical air forces; destroy the remaining ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy; attack strategic targets on the mainland; explore Japanese defenses on northern Honshu and Hokkaido; and destroy Japanese shipping. The British had a sixth mission that was political and diplomatic in nature: support the alliance with the United States. In essence, just taking part in military operations met this goal, but the public needed to know that the United Kingdom was contributing to the fight. Statements that Nimitz released to the press announced attacks as combined U.S.-British operations and identified as many of the British ships taking part as was prudent to make public. In a widely reproduced article, Hanson W. Baldwin, the military editor for The New York Times, would state the Royal Navy was making a significant contribution to the defeat of Japan: “The participation of the British Fleet in the great naval blows against the Japanese homeland represents a psychological, as well as a military, blow to the enemy.”14 He was not alone. The contribution of the British Pacific Fleet to the raids was the subject of page one headlines across the United States.

Logistics, however, would plague the British in the operations against Japan. Halsey was more than willing to help when possible. “One of my most vivid war recollections is of a day when Bert’s [Rawlings’] flagship, the battleship King George V, fueled from the tanker Sabine [(AO-25)] at the same time as the Missouri,” Halsey states in his memoirs. “I went across to ‘the Cagey Five,’ as we called her, on an aerial trolley, just to drink a toast.”

Since the Royal Navy allowed alcohol on board its ships, American officers were always eager to visit. The British made Halsey an honorary member of the officers’ messes of both the battleships Duke of York and King George V. Hard liquor was an asset that served Task Force 37 well. When King George V crewmen were short of a spare part for her radar, they signaled a nearby U.S. destroyer, asking if they could exchange the needed equipment for a bottle of whisky. “Man, for a bottle of whisky you can have this whole goddamned ship,” someone responded on the loudspeaker.15

On the Northern Flank

Combat operations started on 17 July, the day after the British joined up with the Third Fleet. The British formed the Allied combined fleet’s northern flank. The Japanese had fewer airfields in the region of the Home Islands opposite of the BPF, and because Task Force 37 was the weakest formation under Halsey’s command, it made sense to send it north where it would be in less jeopardy. The Americans encountered bad weather and canceled their attacks. Task Force 37 had better luck. Planes from the carriers Formidable and Implacable bombed and strafed airfields and rail facilities on the east coast of Honshu, the biggest of the four main Home Islands. No Japanese fighters greeted these planes, but the antiaircraft fire from the ground was heavy.

Later in the morning, planes from the Formidable and Victorious found clouds and weather obscuring their primary targets, so the pilots flew across Honshu and strafed an airfield in the western coastal city of Niigata. That same day, the King George V along with two destroyers joined U.S. ships to bombard the eastern coast of Honshu. The shelling took place in rain and fog, which made it difficult for aircraft to provide spotting. The bombardment continued for an hour using radar and Loran navigation.16

Aerial missions troubled the British pilots. “The general sensation of being over Japan was one of foreboding, deep fear. We had heard tales of what the locals did to airmen who got hacked down. We got ‘in and out’ as quickly as we could,” Commander R. M. Crosley, the commanding officer of 880 Naval Air Squadron flying off the Implacable, recalled. “We kept below the radar echo height as long as possible so that we did not give warning of our approach. Near the target we split up and climbed to about 8,000 feet and approached in a sort of ‘scissors,’ with aircraft attacking from different angles. Thus we gave the gunners no time at all to get their fingers out before we were gone—not to return.”17

The logistic services of the Royal Navy faced a difficult challenge in keeping up with the pace the Americans were setting. Many of the tankers the British were using had never refueled a ship at sea, and this inexperience slowed down the effort. Rawlings had to ask Halsey if U.S. oilers could assist their effort. The Third Fleet commander agreed, and three cruisers—HMCS Uganda, HMNZS Gambia, and HMNZS Achilles—refueled from American tankers. Fraser knew the strengths and liabilities of both his fleet and that of his allies. “The Commander 3rd Fleet is carrying out a series of operations which both strategically and tactically are designed on the most flexible plan. With easy grace he is striking here one day and there the next, replenishing at sea as the situation demands,” he observed. “With dogged persistence the British Pacific Fleet is keeping up, and if anything is going to stretch its muscles, these operations will. But it is tied by a string to Australia and much handicapped by its few, small, slow tankers.”18

‘A Political Factor’ Affects Ops

During the attacks on Japan, Halsey was determined to destroy what remained of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The admiral had several reasons: national morale demanded revenge for Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy had to have total control of the waters of the North Pacific if it was to have regular supply lines to the Soviet Union, and the enemy fleet had to be eliminated as a bargaining point for the Japanese at a peace conference, as it had been for Germany after World War I. “There was also a fourth reason,” Halsey added, “CINCPAC had ordered the Fleet destroyed. If the other reasons had been invalid, that one alone would have been enough for me.”19

On 18 July, U.S. planes attacked Yokosuka to sink the Nagata, one of the last remaining Japanese battleships. The effort failed and resulted in 12 downed planes. (The Nagata would survive the war and be a target at the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946). Then on 24, 25, and 28 July, U.S. aircraft attacked the Kure naval base. “Kure is the port where Jap warships went to die,” Halsey declared in his memoirs with a glee that still comes across decades later. The Americans sank a carrier, three battleships, five cruisers, and some smaller ships. During these operations, he gave the British secondary targets at Osaka. Task Force 37 performed well in this assignment, setting a record for flying the most sorties in one day, 416.20

In his memoirs, Halsey explains that his chief of staff, Rear Admiral Robert B. Carney, argued against including the British in the Yokosuka and Kure strikes. “At Mick Carney’s insistence, I assigned the British an alternate target, Osaka, which also offered warships, but none of prime importance,” he recalled. “I hated to admit a political factor into a military equation—my respect for Bert Rawlings and his fine men made me hate it doubly—but Mick forced me to recognize that statesmen’s objectives sometimes differ widely from combat objectives, and that an exclusively American attack was therefore in American interests.”21

In making this decision, Halsey acted stupidly—twice. First, in excluding the British from the operations, he clearly confused the institutional interests of the U.S. Navy with the national interests of the United States. There might have been an exceptionally important reason to have the British involved in this operation. More to the point, the operation itself was a mistake. What was left of the Japanese fleet no longer posed any offensive threat to U.S. forces. Even if the war had continued for several months, the Americans who died in these missions spent their lives cheaply on targets of little importance. Halsey’s defense that he only was following Nimitz’s orders rings a bit hollow. As his actions in establishing command arrangements with Rawlings show, there were orders and then there were orders.

Fighting the Japanese and the Weather

Task Force 37 spent 26 and 27 July replenishing its ships. Changes in operations moved the assembly point where the warships would rendezvous with their tankers. “It was a scramble to get finished in the two days allotted,” Vian observed. Rawlings once again had to ask if U.S. ships could help. Halsey quickly replied yes.22

On 29 and 30 July, the King George V joined U.S. ships for a bombardment of Japanese factories in Hamamatsu in southern Honshu. Spotter planes had excellent vision on the bright moonlit night. The battleship took only 27 minutes to fire her salvos and hit everything she was targeting. “Gee-zus—smack on the kisser,” an American spotter pilot had reported after the first salvo hit home. The spotter aircraft, however, had given the British incorrect targeting information. The salvos were tightly grouped, but the production facilities escaped serious damage. An official Admiralty history notes, though, that the indirect effects of the operation resulted in a total halt to production. During this mission, the ships never came under fire from shore batteries or planes.23

On 30 July, the British flew 336 sorties. BPF aircraft stumbled on the Okinawa, a Japanese frigate, and sank her. They also damaged several other vessels. The weather was poor, with significant fog. Wind patterns required that the Implacable steam east into Tokyo Bay to recover all her planes. The rest of Task Force 37 had no choice but to stay with the carrier, while U.S. ships sailed west, creating a huge gap between the two fleets. An aircraft crash on the flight deck slowed recovery operations. When all the planes were on board, Task Force 37 found itself in Tokyo Bay without any fighter cover.24

The Third Fleet then spent the first week in August refueling and trying to avoid typhoons. The bad weather forced Halsey to cancel all operations, while his ships tried to prevent being swamped. For a while it looked as if the British Pacific Fleet would run out of fuel, but another postponement of operations provided enough time for another refueling effort.25

Final, Costly Missions

On 9 August—the day the United States dropped a second atomic bomb on Japan and six days before V-J Day—the planes of the British Pacific Fleet returned to the sky over Japan and suffered one of their heaviest days in losses. The main targets were airfields. The British also attacked several ships as targets of opportunity. The results of these strikes were good; Royal Navy planes sank three destroyers and damaged several others.26

BPF aviators showed exceptional skill and courage on a regular basis. None more so than Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray of the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve, who led one of the 9 August attacks after stumbling on the destroyer Amakusa. Gray, flying an F4U Corsair, went in for the kill, but his plane quickly took fire from shore batteries and from five planes. With his Corsair hit and on fire, the Canadian flew in at a low altitude and scored a direct hit with a bomb that sank the ship. Flames enveloped his plane, and he crashed into the water. Gray, whose body was never recovered, received a posthumous Victoria Cross. “It has always seemed such a terrible shame to me that this quite unexpected chance should have occurred when the war was virtually over,” his commanding officer sadly observed.27

The number of BPF sorties launched per fighter on each strike day had increased dramatically since the fleet had entered the Pacific war. During the Okinawa operations, the Royal Navy averaged 1.08 in March and April, and then 1.09 in May. In July and August, the number jumped to 1.54. “Thus fighter effort was some forty per cent greater in the British operations against Japan than in the operations against Sakishima Gunto,” Admiral Fraser observed in his report to the Admiralty.28

While the British Pacific Fleet’s contribution to the war was more diplomatic than military, that should not obscure an important fact: Despite problems in supply, the British made a credible showing that grew during their deployment. Their strikes did real damage and are another proud chapter in the history of the Royal Navy.

1. Edwyn Gray, Operation Pacific: The Royal Navy’s War Against Japan, 1941–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 236–37; Sir Philip Vian, Action This Day: A War Memoir (London: Frederick Muller Limited, 1960), 197.

2. Peter C. Smith, Task Force 57: The British Pacific Fleet, 1944–1945 (London: Kimber, 1969); John Winton, The Forgotten Fleet (London, Michael Joseph, 1969); Gray, Operation Pacific; H. P. Willmott, Grave of a Dozen Schemes: British Naval Planning and the War Against Japan, 1943–45 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996); David Hobbs, The British Pacific Fleet: The Royal Navy’s Most Powerful Strike Force (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2011).

3. Nicholas Evan Sarantakes, Allies Against the Rising Sun: The United States, the British Nations and the Defeat of Japan (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009), 115–32, 193–216; Notes, 30 June 1945, Folder: Conferences 1944–1945, Box 20, Papers of Ernest King, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

4. Vian, Action This Day, 197; Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 308–9, 333.

5. Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 308–9.

6. Winton, 310.

7. Winton.

8. William F. Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1947), 261–62; Vian, Action This Day, 193; COM3RDFLT to CINCPAC ADV, 16 June 1945, vol. 1 Command Summary, Book six, vol. 3, page 3177, Folder: 3076-3194, Papers of Chester Nimitz, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.

9. CINCPAC ADV to COM3RDFLT, 17 June 1945, vol. 1 Command Summary, Book six, vol. 3, page 3178, Folder: 3076-3194, Papers of Chester Nimitz; Ministry of Defence (Navy), War with Japan, vol. 6, The Advance to Japan (London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1995), 213.

10. CINCPAC ADV to COM3RDFLT, 17 June 1945; Ministry of Defence (Navy), The Advance to Japan, 213.

11. Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 261–62; Vian, Action This Day, 193.

12. Halsey, 262; Vian, 193; Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 313.

13. Halsey, 262; Vian, 193; Winton, 313.

14. Winton, 311; Hanson W. Baldwin, “British Fleet in Pacific,” The New York Times, 23 July 1945.

15. Richard Baker, Dry Ginger: The Biography of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Michael Le Fanu, GCB, DSC (London: W. H. Allen, 1977), 77–78, 82; Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 262; Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 282–83, fn. 1.

16. Smith, Task Force 57, 172–75; Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 316; Vian, Action This Day, 203; Ministry of Defence (Navy), The Advance to Japan, 220–21.

17. Emphasis in original quotation in Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 322; R. M. Crosley, They Gave Me A Seafire (Shrewsbury, England: Airlife Publishing, 1986), 167.

18. Ministry of Defence (Navy), The Advance to Japan, 222; Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 319–20; Vian, Action This Day, 208.

19. Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 265.

20. Halsey, 264; S. W. Roskill, History of the Second World War: The War at Sea, 1939–1945, vol. 3, part 2, The Offensive, 1st June 1944–14th August 1945 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1961), 374–75; Ministry of Defence (Navy), The Advance to Japan, 222–24; Gray, Operation Pacific, 244–45.

21. Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 265.

22. Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 325–26; Vian, Action This Day, 208.

23. Ministry of Defence (Navy), The Advance to Japan, 224–25; Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 327–29.

24. Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 329–30; Vian, Action This Day, 204.

25. Vian, Action This Day, 211–12; Ministry of Defence (Navy), The Advance to Japan, 225–26.

26. Winton, Forgotten Fleet, 335–38.

27. Winton, 337–38; Gray, Operation Pacific, 250.

28. “Commander-in-Chief’s Dispatches—November 1944 to July 1945,” 23 November 1945, ADM 199/118, British National Archives, Richmond, Surrey.